05 Eki EARLY MURNAU REVIEW: A SET FOR THE SILENT CINEPHILE TO LINGER OVER

by Pamela Hutchinson

The concept of “Early Murnau” is a little bittersweet. The German director had such a short career that the films in this new collection from Masters of Cinema take us up to just six years before he died. And while his most famous film was made during the period (1921-25) covered by this box set, that work, Nosferatu, is not included. The set ends just one year before his hypnotic Faust was made, and two before his Hollywood masterpiece Sunrise.

This is technically middle Murnau, then, or “the Murnau you may have missed if you only knew Nosferatu and the surviving Hollywood work”. All the same, this is a gorgeous collection of distinctive, spectacular films, well worth adding to your shelf. All of the films in the set have been made available on DVD from Masters of Cinema previously, but here together, on Blu-ray, they represent a far better bargain.

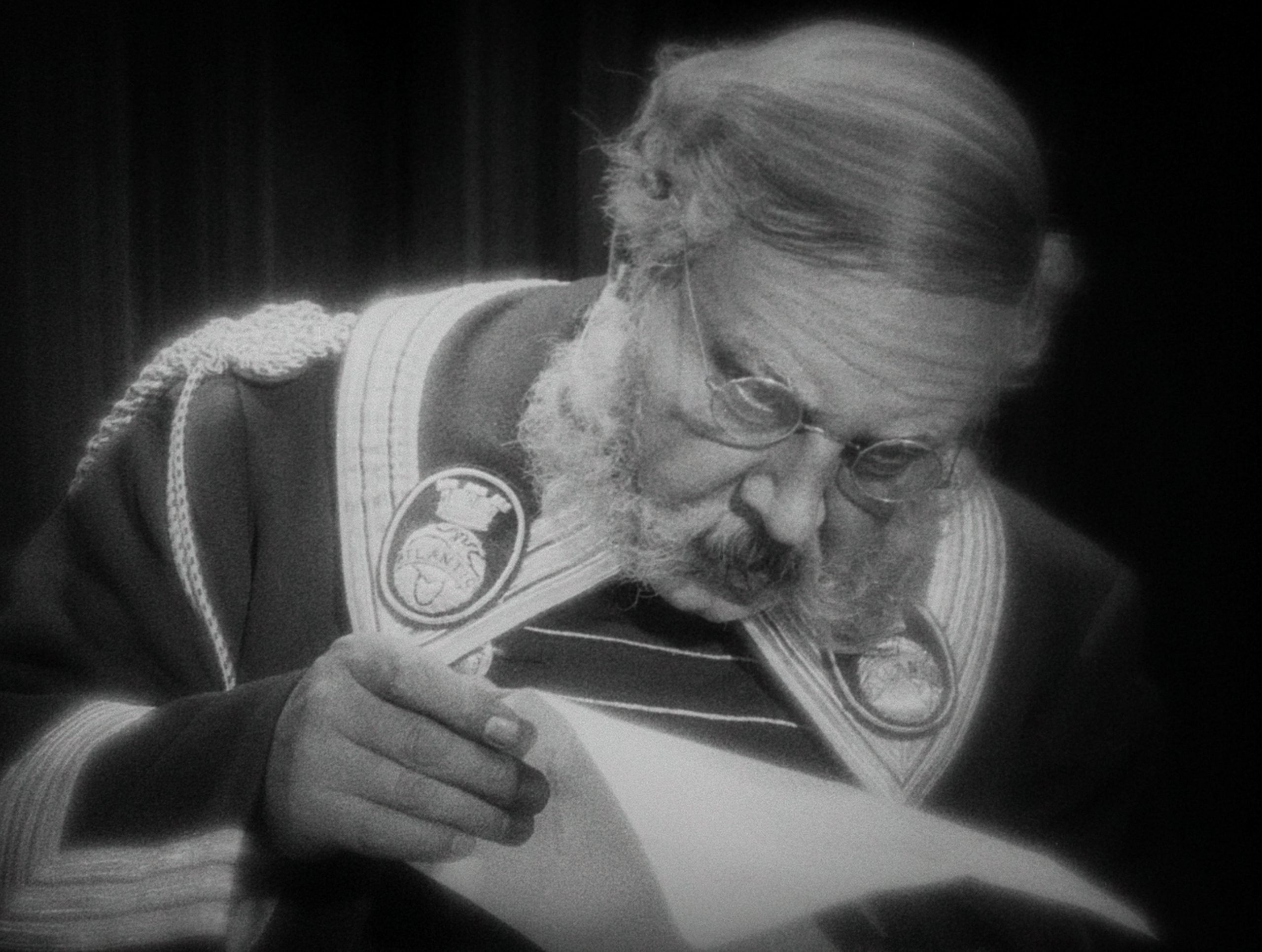

The journey through Murnau’s lesser-sung German work begins in 1921 with Schloss Vogelöd, a country-house mystery rendered mysterious and dreamlike at the director’s touch, and climaxes with the bracing and inventive Molière adaptation Tartuffe (1925), which introduces an especially noxious virtue-signalling hypocrite and hangs him out to dry. In between we delve into the romantic and financial misery of a poetically minded clerk in Phantom (1922), and the related entanglements of an aristocrat in Die Finanzen de Grossherzogs (1924). Indisputably, the highlight of the collection is the low-key masterpiece Die Letzte Mann (1924) starring Emil Jannings as the hotel doorman whose life hits a downward spiral when he is demoted to a toilet attendant.

As the many extra features and essays included with the set attest, Murnau’s oeuvre is hugely varied, swinging from genre to genre and rarely settling in one place for long. Stylistically, though, he is mistakably himself at all times. You can see the walls of the city bend down to oppress the heroes of both Phantom and Die Letzte Mann, for example. And you may already have noticed that the films above share a set of preoccupations with money and social position, with impossible aspirations and with toxic pride.

The faces of these oppressed, haunted characters loom out of the darkness in crisp close-ups, or surrounded by Murnau’s sympathetic murk of spectral apparitions and psychologically motivated special effects. The films here are Expressionistic, but in a very sophisticated way – not the greasepaint and distortion of Caligari, but infused with a subtler, much more uncomfortable disquiet. It’s closer to poetic realism than the Grand Guignol. The set design in Schloss Vogelöd, for example, is stunning, and a dissolving close-up of Lya de Putti in Phantom is a gorgeous as it is unsettling. In an era before horror became a codified genre, Murnau made films that are genuinely disturbing, with shadows that creep where they are not wanted, without swamping and swallowing the frame.

Schloss Vogelöd is perhaps a little slow and stagey for modern tastes, and Phantom is definitely over-long, but both those films more than reward a quiet night in on the sofa – with arresting imagery and gut-wrenching plot twists. Die Finanzen de Grossherzogs reveals that Murnau was incapable of making a film without beauty, but that extended comedy did not come naturally to him. Tartuffe is a true delight, a sharp and human satire told visually (and a valuable lesson in how to turn a stage play into a film, really). Murnau’s decision to place a film within a film gives the satire a modern bite, with Emil Jannings in the deliciously wicked title role. And Die Letzte Mann/The Last Laugh is a triumph that deserves repeat viewing from any serious silent cinephile. It’s a pleasure to see it on Blu-ray and from its dizzy opening sequence, via its heartbreaking middle to its sardonic mockery of a happy ending, it reveals new treasures each time you watch it. Jannings is triumphant, and Karl Freund’s nauseous, roaming, spinning and climbing camera takes the audience to the darkest of emotional spaces.

Highly recommended for anyone who loves Murnau’s better-known work, this a set to linger over. The troubled homes and terrifying cities of these films may seem inhospitable, but as landmarks in the enchanted Murnauland, they offer incomparable cinematic spectacles. Supported by the aforementioned Freund, and by screenplays from Carl Mayer and Thea von Harbou, Murnau made these films for Erich Pommer’s Ufa, and they are all quality productions, sophisticated and elegantly made. The accompanying essays, and the audio commentary by David Kalat on Die Finanzen de Grossherzogs, as well as a smart new video essay by David Cairns, that lingers, understandably on Die Letzte Mann, make it an altogether richer experience.

“Art – authentic art – is simple,” Murnau once said. “But simplicity itself demands artistry.” Other films by the director may be so familiar that we can almost miss the touch of his technique, but the works collected here allow us to understand exactly what makes a Murnau a Murnau.

This article is taken from Silent London.