20 Eki CINEMA’S FIRST EPIDEMIC: FROM CONTAGIOUS TWITCHING TO CONVULSIVE LAUGHTER

By Maggie Hennefeld

There was no funnier sight gag in early cinema than the catastrophe of epidemic contagion. In The Yawner (1907), a man’s involuntary yawning transmits irresistibly to his housekeeper, a squadron of military soldiers, day drinkers at a café, a police officer, and an inanimate portrait of a woman, who’s roused from her stasis by the impulsion to yawn. Habitual tics such as yawning, laughing, sneezing, hiccupping, itching, coughing, barking, sobbing, and blinking spread like wildfire when too many nervous bodies found themselves together in close quarters. In Laughing Gas (1907), a black woman’s joyful hysterics steamroll the public sphere — convulsing white workers, black gospel revelers, and several police officers — after her dentist gives her nitrous oxide (a.k.a. laughing gas) during a tooth extraction. The craze for tango dancing, of all things, possesses hot-to-trot bodies in The Epidemic (1914), while That Fatal Sneeze (1907) takes the perils of involuntary outbursts to their mortal conclusion. (A man dies from sneezing!) The point is that any such bodily symptom was fair game for epidemic exposure — from a sneeze or a yawn to a belly laugh and the penchant for tango dancing.

Should we find it disturbing that these movies were all comedies? What’s so funny about the vulnerability of isolated bodies succumbing to the spastic will of the roiling masses? Just as zombie movies and other grossly corporeal films evoke anxious dread and clammy discomfort, a little haphazard excess can go a long way toward tipping the balance from horror to slapstick. But what is the line between anxiety and enjoyment when it comes to the spectacle of hysterical bodily contagion?

Laughter is often described in suspiciously hysterical terms. The euphemism first took hold in the late 19th century when the notion of laughter as “hysterical” shifted in meaning from nervous breakdown to convulsive enjoyment. Prior to that time, “hysterical laughter” was the last thing you ever wanted to experience with your body. It rang out in anguished peals from psychiatric asylums to incidents of mass psychogenic illness, such as the 1787 Cotton Mill Outbreak and 1962 Tanganyika Laughter Epidemic. Neither entirely real nor purely illusion, hysteria lingers in that gray zone between anxiety and transmission. This is no doubt what also makes it ripe terrain for comedy.

Comic pantomime has a foothold in mimicry, which is likewise essential to the symptomology of hysteria. From the Greek word for uterus (hystera), physicians believed a woman’s womb could start wandering around her body in cases of dormancy or disuse. A pestilence among spinsters and widows, it further made mischief by imitating organic processes of the zones it traversed; for example, if the womb got into the throat, it might create a sensation of choking (i.e., “globus hystericus”). If it got into the foot, it could trigger either paralysis or dancing mania, spreading contagiously like in the 1518 Dancing Plague or 1374 Dancing Mania that shadowed the Black Death. Incidentally, tango and polka dancing were among the foremost hazards of slapstick contagion comedies (see Kristina Köhler’s extensive research on this topic). Whether comic or tragic, the notion of hysteria has long conveyed a severe disorientation between suggestible mimesis and organic affliction. Is the patient truly suffering, or merely a malingerer? Hysteria’s hallmark is imitation, further implicating it as a prime suspect — and inevitable whiplash — amid mass outbreaks of epidemic disease.

Affective Contagion in Early Film Comedy

In the very early 20th century, the mass migration of people and rapid swarming of laboring bodies into fast-paced, capitalist cities provided a groundwork for the visual catharsis of epidemic-themed comedies. There’s something uniquely therapeutic about the absurd spectacle of bodily contagion when enjoyed from a distance. Cayenne Pepper in a Street Cab (1903) lampoons the nervous attractions of sneezing when a lady with armful of groceries accidentally drops her package of cayenne pepper on an overly full street car. The result is an “epidemic of sneezing among the passengers, which is more easily imagined than described,” boasted the Selig Polyscope Company.

But affective suggestion also served as a breeding ground for conspiracy theories and xenophobic attitudes. Gustave Le Bon compared the contagion of ideas, sentiments, and emotions to “microbes” in his 1895 study of crowd psychology. Gut feelings gain momentum in the petri dish of modern crowds, where unschooled passions are given free rein over elitist expertise. Early films depict these teeming hazards of mob psychology in purely somatic terms. A Contagious Nervousness (1908) burlesques the explosion of anger that germinates from a husband and wife’s domestic squabble, but quickly spreads to essential workers and eventually barnyard animals. Other epidemic-themed comedies hilariously mistake the contagion for the cause. An All-Wool Garment (1908) pulls a bait-and-switch between affect and underwear, when a gentleman is so tormented by his itchy new garments that his office co-workers, streetcar passengers, and even fellow movie spectators cannot resist that urge to scratch. Confusion between device and transmission comes full circle, the crisis resolved by the man’s purchase of new cotton skivvies. Never mind the unruly masses of prickling bodies who’d never donned itchy garments in the first place. Their compulsion to relieve themselves is collateral damage from the desire to imagine dangerous affective contagion in ludicrously epidemic terms.

Neurasthenia and hysteria were often viewed as wastebaskets for any unexplainable ailment, meaning that if you couldn’t accurately diagnose, then hystericize it. Potential symptoms ranged from somnambulism, paralysis, and hallucinations to political excitement, novel reading, and “masturbation & tobacco.” Mysterious in origin, overdetermined in meaning (from displaced desire to overt defiance), and unpredictable in transmission, the amorphous morphology of hysteria rendered the disease dually fascinating and horrifying. Endemic ambivalence about epidemic hysteria was not lost on early filmmakers of slapstick comedy, who harnessed film’s spreading popularity despite the rampant anxieties about its toxic immorality.

How to prove that nervous contagion is innocuous? Make it fun! Theater exhibitors even advised turning up the houselights so viewers could espy their neighbor’s writhing, spasmodic body and then “no longer keep laughs exclusively to themselves.” Similarly, a man’s neurotic disorder afflicts “all within sight” in Contagious Nervous Twitching (1908), according to The Film Index. His involuntary tic has roughly the same effect as a woman’s fetching physique in A Very Fine Lady (1908), where her public presence provokes men’s libidinous ogling and causes a disastrous disruption of work. In contrast, the nervous twitcher wreaks havoc through mimetic bodily contagion. A janitor catches his knee twirl and topples down the stairs; a hod-carrier mounted atop a ladder contracts his spastic convulsions and then plasters a surveying architect in mortar; a wedding party turns into an epileptic orgy; and so forth. Affective suggestion animates even the inorganic, as in The Yawner, convulsing a concrete statue into a neurasthenic tableau-vivant. Do germs reside in our living bodies or in the spaces we inhabit? Whether corporeal or environmental, the man’s nervous twitching lands the whole public sphere in his neurologist’s office by the end of the film.

Archiving “Epidemics”: Fatal Germ or Financial Gimmick?

There was no greater selling point for a slapstick film comedy than comparing its laughing effects to those of an epidemic. Viewers flocked to watch ludicrous contagion gags that promised to incite uncontrollable audience laughter. For example, A Flirty Affliction (1910) — which is basically a gender-reverse remake of Contagious Nervous Twitching, in which a young woman’s facial spasms are mistaken for sexual flirting — was guaranteed to “send a convulsive epidemic around the audience,” according to The Nickelodeon. The Vitagraph comedy Grin and Win (1909), about a “sour-faced family” who buys a Billiken that enthuses them to radiate happiness, will “cause a hearty laugh,” promised The Moving Picture World. “The spirit of the thing is contagious and before the audience knows it everyone is laughing.” Likewise, in Matrimonial Epidemic (1911) — a slapstick comedy about epidemic matrimony — “the love germ finds lodgment and develops to laughable proportions.” Last but not least, Seven Days (1910) was described by The San Francisco Dramatic Review as a “raging epidemic of fun, laughter, merriment, and all other jolly complications.” Affective contagion offered a lucrative gimmick for voracious film advertisers, and pandemic-themed sight gags were their ace in the hole.

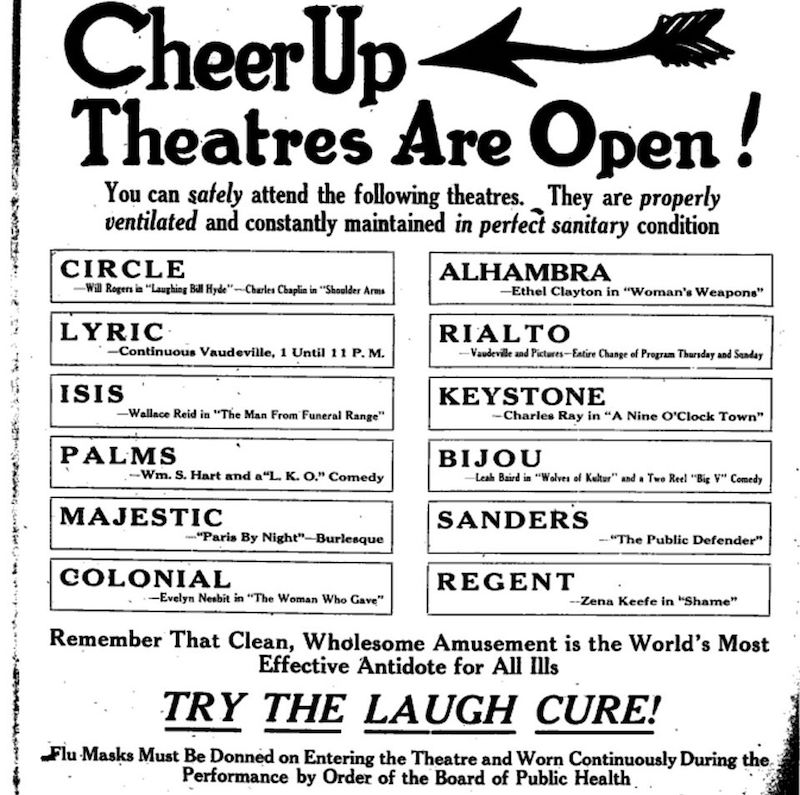

Though clearly the ploy of an expanding capitalist industry, hyperbolic metaphors collided headlong with tangible outbreaks of deadly disease. Even before the 1918 influenza plague, recurring waves of illness repeatedly threatened the livelihood of filmmakers and exhibitors. Polio bedeviled the industry from 1912 until long after the 1918 flu outbreak. Children under 16 were even banned from going to the movies. “The infantile epidemic has done a great injury to show business,” reported Variety in 1912, “result[ing] in the police issuing an order preventing children under 15 from attending local theatres.” Partial closures, age-based prohibitions, and other safety precautions were implemented on temporary and regional bases across the United States. The Moving Picture Weekly described polio in 1917 as “one of the most serious menaces which has ever faced the moving picture exhibitors,” lamenting the steep decline in “daily receipts” caused by the loss of juvenile attendance. In summer 1918, it was again infantile paralysis — not influenza — that mandated theaters to close for over a month across the country, from New York to Iowa to California.

Perhaps it was polio’s slow-burn incitement to partial quarantine that provoked exhibitors to remain somewhat cavalier in the face of influenza. In December 1918, The Springfield News-Record published a scandalous editorial, “Common Sense and the ‘Flu’,” declaring that “[p]atience has ceased to be a virtue” and describing mandatory closures as “ridiculous.” Portentous symptoms were debated not for their contagion but for their unpredictable timing. “How is a theatre manager to know whether a patron has a cough by looking him in the eye?” lamented one nervous employee, and “How can he tell whether or not the ticket holder will sneeze while he is in the place?” As we remember from Cayenne Pepper in a Street Cab, the impetus for a sneeze can run the gamut from nervous suggestion to digestible condiments.

In the early 20th century, typhus, yellow fever, cholera, influenza, polio, measles, and rubella all loomed large as mortal threats to public health that individuals might contract in any communal space — from the streetcar, to the marketplace, to the cinema. The rise of seedy, store-front “nickelodeon” theaters in 1905, where spectators crowded like sardines into unventilated rooms, raised further public health concerns about insanitation. Scarlet fever closed a swath of movie theaters in Chicago in 1906, in New York City in 1907, in Ohio in 1910, and Omaha in 1917, where an alliance of exhibitors won an appeal against regional commissioners to keep the theaters open. Then as now, economic incentives butted heads with public health precautions.

This piece was written in March–April 2020, before the global political uprisings against white supremacy, police brutality, and structural racism erupted in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. I very much see the recent protests — which have radiated poetic anger and resilient spontaneity — in the vein of a “carnivalesque general strike” that parlays affective contagion into collective solidarity.