16 Eki FILMATIQUE: INTERVIEW WITH PRANTIK NARAYAN BASU

Intervıew by Rıtıka Bıswas Guest Curator, Fılmatıque

Prantik Narayan Basu is an Indian screenwriter, cinematographer, editor, and film director. Having studied Film Directing at the Film and Television Institute of India, his short film Sakhisona premiered at BFI London, Mumbai, and Rotterdam, where it won the Tiger Award for Best Short Film. Rang Mahal (Palace of Colours) premiered at Berlin, IDFA, Signes de Nuit Thailand, Concorto Film Festival, DMZ Docs, Nomadica Bologna, Arthouse Asia, and Bilbao International Festival of Documentary and Short Films.

Prantik Narayan Basu participated in an exclusive interview with Filmatique as part of Talents 2020.

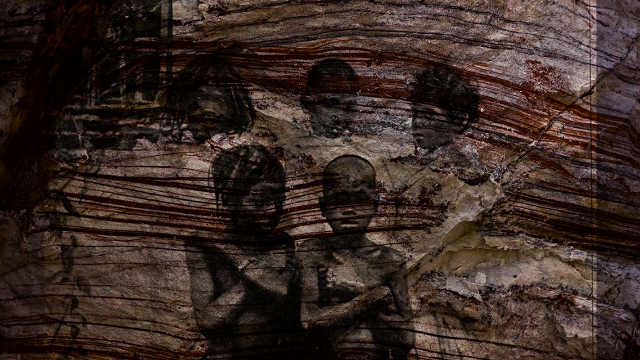

FILMATIQUE: Thank you for sharing your films. Rang Mahal (Palace of Colours) was quite mesmeric to watch—dreamy and alluring in its meditation. To me Sakhisona laid out the lexicon in some ways for Rang Mahal in terms of its fabulistic, mythical and nonhuman aspects. I’d like to start with the architecture of myth, history and land in Rang Mahal—how did you construct it? What was your process going into that?

PRANTIK NARAYAN BASU: The pleasure is mine. I like the reference to architecture. I think about it often, as films unfold in time and space as well. My practice has been closely associated with myths and folklore. They work as a time capsule, an access to the anecdotal history and gives us an access to the ethos of a community. I love reading/listening to them, and as a filmmaker, I always like to share what I love.

Most of these timeless tales are not only a structural marvel, but way more progressive than many of our contemporary narratives. For instance, the creation myths in Rang Mahal speak of a harmonious co-existence of nature and human, where the human is not at the center of the narrative. Our popular viewing culture has put humans at the center of every narrative. Cinema, I believe, is capable of going beyond this to envisage the narrative possibility of an altered frame of reference.

Khori Dungri, or the chalk stone hill that we see in the film is formed through years of erosion and sedimentation. Its pigments are used by the locals to mend and adorn the cracks on the walls of their houses. Like those rocks that come in various hues, there are myriad versions of the Santhali creation myth. I asked some people from the community and they revealed that since these myths pass on orally, they vary in their telling and retelling. I was fascinated by this idea, of having various versions of the same story. While this became the aural layer, I started to build upon the image layer with rocks, hills, trees and the village, sometimes in direct relation to the story, and sometimes leaving it open-ended for the viewer to interpret their own version.

FLMTQ: I like this notion of erosion, as I was thinking about the quite accretional mode of your film—accretional in the sense that the film is layering the fabulistic and the mythical, but doing so not in an ethnographic or documentary way. It was very lived, very present and immersive. And it was also being layered with the topography of the space, and the space itself telling its own stories of temporality.

My question here arises from an essay by Ashis Nandy, “The Landscape of Clandestine and Incommunicable Selves,” which talks about the colonial project of rational enlightenment. This project deemed the myths, superstitions, and folklore of the colonized as apolitical or ahistorical, as not rational according to their notions of hierarchies.

Whereas your films meld folklore and history—of course this is history, it’s how people are living and have lived. It’s how they believe and how they construct their lives. Can you tell me how you came to that thinking in terms of folklore and oral storytelling as the history of an entire people, or entire generations of people who live in rural nonhuman places? How history is constructed in a way that we don’t think about or consider as textbook history or state history?

PNB: So, if we just consider the ritual in itself, the Santhals look at this as a kind of repair, both literal and metaphorical. The fact that these myths are retold on the festival days of Sohrai (a late harvest festival) also points towards myths as microcosms. For instance, the Thakur Jivi story in Rang Mahal points out clearly that the deity created animals first and only then did humans enter the picture. Santhals are extremely self-aware about their status as interlopers on this planet, and that also shows in their harmonious relationship with the environment. For them, a tree is not just a tree, nor is a pond a mere hole on land in which to store water; they are associated with more familial values.

For too long, we have convinced ourselves that we know what ‘development’ means in the Adivasi (indigenous) context. In this regard, it is important to mention the Pathalgadi (stone slab) movement, wherein many Adivasi villages in India have declared themselves ‘self-rule zones.’ The sections of the Constitution of India that give them the right to self-rule are inscribed onto large stone slabs, often placed right at the village entrance. Ironically, a community that had no written language until recent years is writing their own history as we speak, and we can only hope that one day the world will sensitize itself enough to recognize that belief systems other than our own exist, and are probably wiser and more sustainable in the long run.

FLMTQ: That is a notion that is direly needed and I think incredibly lost in this late-capitalist extractivist world. A lot of eco-justice movements aren’t about trying to find new solutions or looking toward some post-human future. It’s literally a matter of going to indigenous communities and asking them, how have you lived? Because they are living in oneness, they are living in a non-exploitative way with the nonhuman, and they’re not separate from it.

A lot of indigenous knowledge is kind of coming into play now, whereas before it was very marginal and peripheral to the mainstream, or even independent art world or film world, or literary worlds. So how do you approach a community, but not necessarily with the gaze of being an ethnographer, or not making them look primitive or atavistic? Because those are very reductive ways in which people have often considered tribal communities in various parts of the world. What was your approach, knowing that?

PNB: The first approach was of course being aware of it. I have grown up in a suburban setting and I cannot claim to fully understand their issues. The dynamics of their relationship with nature is very complex. What I could do at best was not to be a ‘colonizer’ myself with my tool—the camera. Since I have been working closely with the community for quite some time now (firstly in Sakhisona and then in another documentary that is presently in post-production), there has been a certain sense of camaraderie. My main attempt was not to intrude or probe into their shyness, which would have been perverse, in my opinion. The moment we approach a community as a cumulative subject and put ourselves in the milieu with our camera, we assume a position of power which prevents any fluid interaction. This is seen in the archival portraits that I used in the film as counterpoints. I wanted to refrain from that very act, which is why I have not used humans as my subjects, but only their voices that are seldom heard in the mainstream. I find it problematic to make them stand in front of the camera and shoot their features. Hence, I chose to film from a certain distance and present the world as it is. I believe it helped me achieve more intimacy and understand their world as they see it, a little more than I did before.

FLMTQ: Speaking of this foray into a way of life that we might learn from, I found your soundscape and sound design quite fascinating—you had the voiceover and the folklore, but there was so much emphasis and constant attention and nuance given to the sounds of trees and birds and insects, this constant tapestry of sound. Which to us might just be noise, but it is also a language of its own. Was that something you were intentionally playing with?

PNB: This is something my sound designer Ananda Gupta, and I discussed at length, and arrived at after a lot of trial and error. That natural sounds would play a vital role along with the narration was part of the plan, but to what effect is something that we decided along the process. The voices of Balika Hembram and Sanjay Tudu have a certain lyricism and an intimacy of telling a story to a friend. This allowed us to dream away and imagine a soundscape for the story being narrated, almost in the manner of a radio play. But here we have the visuals, that sometimes compliment and at times contradict what we hear. Simply put, you can say that we were being playful.

FLMTQ: So you’re working on the long documentary, is that coming out next?

PNB: Yes. I just finished editing it and as soon as the lockdown ends, we shall finalize the sound design, color grading et al. It is called Bela and is a film on the group of dancers who featured in my previous film. This too is an observational portrait of a small village by the same name, their rhythms and rituals of art and labor, and the ambiguous threshold between them.

I also finished writing the script of my first fiction feature Dengue, which received the Hubert Bals fund from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. It is the story of a chance encounter between two men during a sudden summer rain that leads to a feverish romance. I developed the project at the PJLF Three Rivers Residency in Italy and we plan to go into production next year.